Recusal during investigative action

Quodcunque aliquis ob tutelam corporis sui fecerit jure id fecisse videtur

- everything that a person does to protect himself is considered to be done legally (lat.)

During pre-trial proceedings, grounds often arise for challenging the investigator, but it is generally accepted that this is a completely futile undertaking, because it is doomed to a deliberate refusal. However, in some cases it is not devoid of common procedural sense when it is implemented directly during the investigative action. The author of this article gives examples of the use of illegal methods by an investigator during a confrontation and tells how to counteract investigative arbitrariness by means of a challenge to an investigator during an investigative action, and in what situations to use the procedural institution of extreme necessity.

Illegal methods in confrontation

In my practice as a lawyer, there was perhaps the most dramatic confrontation that took place in a temporary detention center between an accused bribe-taker and a witness bribe-giver. The whole difficulty of participation lay in the personality of the investigator, who replaced the norms of the criminal process with his own concepts and stubbornly did not want to deviate from them.

When I began to consistently ask numerous questions to the witness and obtain the testimony necessary for the defense, the investigator, without recording them, violating the established procedure, began asking his own clarifying, and most often leading, questions that threatened criminal prosecution. The witness, frightened by this, and already showing sympathy for the investigator, willingly refused the answer given to me, and the investigator recorded precisely this “modernized” testimony of his. At some point, I had to stand behind the seated investigator in order to control his writings, which were displayed on the monitor screen. Then, having received an undesirable answer from the witness, the investigator brazenly and unceremoniously declared that I had heard him incorrectly, and wrote down everything exactly the opposite, or allowed himself to answer for the witness, and then, without a shadow of embarrassment, tried to convince me that this is exactly what the witness testified, and For some reason I listened to this. When my questions seemed dangerous to him, he easily dismissed them, accompanied by the standard phrase “not relevant,” although they were relevant—most directly.

My indignation knew no bounds, but the keyboard and computer mouse were in the unlimited possession and use of the person conducting the confrontation. In response to this, I emotionally expressed objections to his illegal actions, spoke about the inadmissibility of interrogating the defense lawyer, asking leading questions, demanding that he record verbatim testimony given, threatening to write complaints and bring him to disciplinary liability, which, however, didn't bother me at all. The usual confrontation, which initially presented no difficulties, turned into an exhausting battle for every word and lasted about 4 hours. Frightened police officers from the detention center periodically came into the office, finding out if everything was okay with us and whether their intervention was required.

At the end of the confrontation protocol, I had to write multi-page comments and additions, and when leaving, promise to reward the investigator with the pennant of “the worst in the history of the prosecutor’s office and the investigative committee,” predicting his speedy end to his career.

My predictions turned out to be prophetic, since after a short time the investigator was thrown out in disgrace for massive falsification of protocols in other cases, but my petitions to exclude the protocol from the evidence and to conduct a repeated confrontation were left unsatisfied: the investigator and his boss were completely satisfied with the answers witness to the official's questions, and they were not at all interested in the answers to the defense lawyer's questions.

Here is another example that took place in the practice of my colleague. The investigator, bringing charges against a person with the participation of his defense attorney, frankly stated that he was charging him with a crime provided for in addition to Art. 222 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation, also part 2 of Art. 105 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation, but understands that the accused did not commit murder, but he cannot leave this crime unsolved. In response to these confessions, the indignant prisoner began to express to the investigator the worst words and phrases known to him, earning an additional punishment under Art. 319 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation (insulting a government official).

The examples given make us think about what procedural means the defense may have to counteract investigative arbitrariness.

Countermeasures

We know that a witness (victim), when testifying during an interrogation, under the influence of an investigator or other circumstances, can easily sign a knowingly false testimony. There is no need to further explain how important a confrontation in such a case may be for the fate of the accused. Conducted using illegal methods, it may be the basis for reading out the testimony of a witness (victim) who did not appear, and the court will not be able to directly hear his testimony and, as a result, may pass an unjust verdict.

In this regard, when during the course of this investigative action procedural rights are grossly violated, the protocol and testimony in it are distorted, then extraordinary measures are necessary.

Among them, I would confidently include a statement of challenge to the investigator during the investigative action.

Part 2 of Art. 61 of the Code of Criminal Procedure of the Russian Federation provides: “The persons specified in the first part of this article (including the investigator) cannot participate in criminal proceedings also in cases where there are other circumstances giving reason to believe that they personally, directly or indirectly, interested in the outcome of this criminal case"

.

In accordance with Part 1 of Art. 67 of the Code of Criminal Procedure of the Russian Federation: “The decision to challenge an investigator is made by the head of the investigative body...”

.

According to the requirements of Art. 121 of the Code of Criminal Procedure of the Russian Federation: “The petition is subject to consideration and resolution immediately after its application...”

.

Based on these procedural norms, a challenge to an investigator is possible when, during a confrontation, circumstances are discovered that indicate bias and partiality in one or another of his illegal actions and decisions, and even more so an intention, by distorting the testimony of a witness, to convict the accused of committing a crime that he did not commit or create artificial evidence of his guilt.

Having received evidence of the investigator’s interest, the defense attorney, before completing the confrontation, draws up a reasoned challenge to the investigator on a separate sheet of paper, transfers it to the investigator and demands to suspend the investigative action and organize consideration of the challenge, transferring it to the head of the investigative body.

It is not difficult to guess that the average investigator will want to continue conducting the confrontation, and will offer to file a petition for his challenge after its completion. But a defense attorney may take a principled position on the need to consider a challenge, not wanting to participate in an illegal confrontation.

It would not be out of place to note that criminal procedural norms have completely distanced themselves from regulating this situation, and therefore there is no reason to believe that the request made by the lawyer during the investigative action is an abuse of law.

Previously, in the Advokatskaya Gazeta there was already a rather interesting discussion about the right of a lawyer to leave the place of investigative action between respected Moscow lawyers Nikolai Kipnis Shocking or procedural necessity1 and Boris Kozhemyakin A lawyer cannot leave the defense2. Nikolai Kipnis, and then Henry Reznik, defended the legality of the termination of proceedings by the disciplinary bodies of the Moscow Bar Association against a lawyer who, having discovered the groundlessness of the charges brought against his client, immediately challenged the investigator, but it was not considered, after which the defender independently suspended his participation in investigative actions3.

Respected Boris Kozhemyakin condemned the actions of the lawyer, believing that they were more shocking than procedural necessity.

Of course, you should always keep in mind that a lawyer’s departure from an investigative action if the investigator or his superior fails to take measures to resolve the requested challenge may become a reason for disciplinary proceedings in the bar association.

Some qualification commissions advocate an unconditional ban on such behavior for lawyers. However, there is no rule without exception, and the Moscow Bar Association demonstrated this in the above disciplinary case.

It seems to me that the legality of a lawyer’s actions should directly depend on the degree of arbitrariness of the investigator’s actions and on the depth of his violations of the law and procedural rights of the defense.

If during a confrontation the investigator rejected a couple of questions from the lawyer, to which the latter was offended, challenged him and left, then such behavior is unlikely to find understanding in the qualification commission.

If the investigator, throughout the course of the confrontation, systematically rejected relevant questions, not allowing the circumstances important to the case to be clarified, refused to record the witness’s answers, significantly distorted them, answered the questions asked of the witness himself, in fact, in the presence of the defense lawyer, falsified the evidence in the most rude and unceremonious manner guilt of the accused, then the inaction of the lawyer in this case can be regarded as faulty behavior, contrary to the requirements of Art. 8 of the Code of Professional Ethics for Lawyers that a lawyer is obliged to honestly, reasonably, conscientiously, skillfully, principledly and timely fulfill his duties, actively protect the rights, freedoms and interests of clients by all means not prohibited by law, guided by the Constitution of the Russian Federation, the law and this Code.

To properly resolve such situations, it is necessary to use a procedural institution of extreme necessity, when, in order to prevent significant damage to the interests of the client and, possibly, the subsequent issuance of an unfair judicial act, the lawyer, having challenged the investigator and without waiting for his permission, leaves the place of the investigative action, probably forced and harming other protected interests.

At the same time, he does not refuse the defense, does not oppose the investigation, but thus forces him to consider the requested challenge and only then plans to continue his participation in the defense.

For strict adherents of lawyer's piety, I will immediately say that such problematic situations are excluded where the investigator respects the rights of the defense, procedural law and by virtue of Part 1 of Art. 8 of the Code of Criminal Procedure of the Russian Federation provides the possibility of exercising these rights.

In my opinion, the position of those disciplinary bodies that strictly evaluate deviations from the established legal and ethical standards of lawyers, but do not take into account the illegality of the actions of officials who provoked retaliatory actions by defense lawyers, is erroneous.

There is also an important practical aspect to recusing the investigator. After his statement and demand for immediate permission, the investigator will be in danger of disrupting the investigative action. It is possible that this could violate procedural deadlines and create serious problems for him.

Understanding this, a thinking lawyer at some most convenient moment has the opportunity to compromise with the investigator: refuse to challenge in response to the fact that the official will continue to conduct a confrontation in compliance with the requirements of the procedural law, will not challenge permissible questions, etc. .

Ideally, such an outcome is the most acceptable for the defense, and the petition for recusal serves the investigator as a sobering shower for Charcot.

* * *

If you do not take active offensive actions, but limit yourself to writing comments on the protocol of the investigative action, which is what I did, then the likelihood of recognizing the tendentiously printed protocol of the confrontation as admissible increases

and reliable evidence. Unfortunately, the relevant investigative and judicial practice is well known to us...

1 "AG". 2014. No. 21.

2 "AG". 2014. No. 24.

3 Disciplinary proceedings. 2012. No. 9/1406.

From the editors We invite you to discuss this topic on the website advgazeta.ru

Complaint about unlawful actions (inaction) and procedural decisions of the investigator

In accordance with Article 123 of the Code of Criminal Procedure of the Russian Federation, a defense lawyer may file a complaint against the actions (inactions) and decisions of the inquiry body, the inquiry officer, the investigator, the prosecutor and the court.

By definition T.T. Alieva, N.A. Gromov and L.V. Makarov “a complaint is a reasoned objection of a participant in the process, brought against the actions (inaction) of an authorized official or body, filed in the manner prescribed by law, orally or in writing” [4].

As a rule, most often at the stage of preliminary investigation of a criminal case, lawyers file a complaint against the actions of the investigator (or his inaction and procedural decisions).

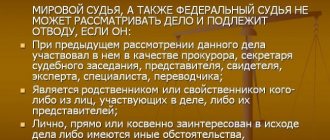

Article 64 of the Code of Criminal Procedure of the Russian Federation. Application for recusal of a judge

- If there are circumstances provided for in Articles 61 and 63 of this Code, the judge may be challenged by participants in criminal proceedings.

- The challenge to the judge is declared before the start of the judicial investigation, and in the case of a criminal case being considered by a court with the participation of jurors - before the formation of a panel of jurors. During a further court hearing, an application for challenge is allowed only if the basis for it was not previously known to the party.

Article 69 of the Code of Criminal Procedure of the Russian Federation. Translator's recusal

- The decision to challenge an interpreter during pre-trial proceedings in a criminal case is made by the inquiry officer, investigator, as well as the court in cases provided for in Article 165 of this Code. During judicial proceedings, this decision is made by the court hearing the criminal case or the judge presiding over the jury trial.

- If there are circumstances provided for in Article 61 of this Code, the translator may be challenged by the parties, and if the translator is found to be incompetent, by a witness, expert or specialist.

- A person's previous participation in criminal proceedings as a translator is not a basis for his recusal.

Article 65 of the Code of Criminal Procedure of the Russian Federation. Procedure for considering an application to challenge a judge

- A challenge filed against a judge is resolved by the court in the deliberation room with the issuance of a ruling or resolution.

- A challenge filed against a judge is resolved by the remaining judges if the criminal case is considered by the court collectively, in the absence of the judge to whom the challenge was filed. A judge who has been challenged has the right, before the remaining judges are removed to the deliberation room, to publicly state his explanation regarding the challenge filed to him.

- A challenge filed against several judges or the entire composition of the court is resolved by the same court in its entirety by a majority vote.

- A challenge submitted to the judge solely considering a criminal case, or a petition for the application of a preventive measure or investigative actions, or a complaint against a decision to refuse to initiate a criminal case or to terminate it, is resolved by the same judge.

- If an application to challenge a judge, several judges or the entire court is satisfied, the criminal case, petition or complaint is transferred to the proceedings of another judge or another court, respectively, in the manner established by this Code.

- If, simultaneously with a challenge to a judge, a challenge is filed against one of the other participants in the criminal proceedings, then the issue of the judge’s challenge is resolved first.